This week's readings | Australasian road movies

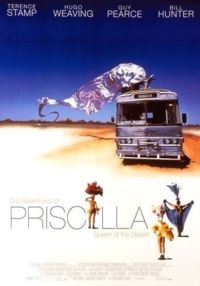

The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994)

Running on Empty (John Clark, 1982)

Doing Time For Patsy Cline (Chris Kennedy, 1997)

Welcome to Woop Woop (Stephan Elliott, 1997)

Roadgames (Richard Franklin, 1981)

Kiss or Kill (Bill Bennett, 1997)

Backroads (Phillip Noyce, 1977)

Heaven's Burning (Craig Lahiff, 1997)

Japanese Story (Sue Brooks, 2003)

Beneath Clouds (Ivan Sen, 2002) 90 min.

The road movie has only been quite recently identified as a distinct type of film, perhaps as late as 1991. In fact, some significant writers do not identify it as a genre at all. Steve Neale does not mention it at all in any of his three books on film genre, except for one sentence (in Neale 2000), where he simply states in passing, right near the end of the book, that "Wild at Heart is a road movie ..." (250). In Cook & Bernink's The Cinema Book, to which Neale is a major contributor, "road movie" does not even appear in the index, although there is major treatment of several other types of film.

The situation is quite different, as you would expect, in The Road Movie Book, in which Cohan and Hark treat this as a genre in its own right. When it does first emerge as such, in Corrigan (1991), for example, it is defined by mise-en-scene:

Road movies are, by definition, movies about cars, trucks, motor cycles, or some other motoring self-descendant of the nineteenth-century train. (Corrigan 1991: 144, as cited in Cohan & Hark 1997: 3)

I want to pause a moment to stress this hypothesis, as it's one I don't think anyone else has noted: that the road movie is defined in the first instance by its mise-en-scene. If you look again at the quotation I use from Robert Stam in the first chapter of Ten Types, you'll see that he suggests a number of different ways of deriving generic characteristics, but mise-en-scene is not among them: "location" is as close as he gets. And yet the primary feature of the road movie as Corrigan points out is that minimally it has a road and a vehicle.

I want to further suggest that the road movie has this in common with its cousin, the western, that it is like a stage on which many different kinds of play can take place. As Cohan & Hark suggest: "... the road movie genre takes over the ideological burden of its close relation, the Western." (Cohan & Hark 1997: 12) But whereas it seems to me that the type of play typically found on the western stage is the morality play, in which some ethical problem is posed and then resolved, on the road stage, the play is more likely to concern a journey of discovery. The discovery can, however, be made in any field of human endeavour. Here are Cohan & Hark again: the road movie genre is "... a productive ground for exploring issues of nationhood, economics, sexuality, gender, class, and race. (Cohan & Hark 1997: 12) So, once the defining feature (road + vehicle) is noted, the inquiring human mind is quick to make connections of other kinds, as in Corrigan himself.

According to Corrigan, "the road movie is very much a postwar phenomenon" (143), and it finds its generic coherence, he explains, in the coalescence of four related features that connect the genre to the history of postwar US culture. A road narrative, first of all, responds to the breakdown of the family unit, "that Oedipal centerpiece of classical narrative" (145), and so witnesses the resulting destabilization of male subjectivity and masculine empowerment. Second, "in the road movie events act upon the characters: the historical world is always too much of a context, and objects along the road are usually menacing and materially assertive" (145). Third, the road protagonist readily identifies with the means of mechanized transportation, the automobile or motorcycle, which "becomes the only promise of self in a culture of mechanical reproduction" (146), to the point where it even becomes "transformed into a human or spiritual reality" (145). And fourth, as "a genre traditionally focused, almost exclusively, on men and the absence of women" (143), the road movie promotes a male escapist fantasy linking masculinity to technology and defining the road as a space that is at once resistant to while ultimately contained by the responsibilities of domesticity: home life, marriage, employment. (Corrigan 1991, as cited in Cohan & Hark 1997: 2-3)

So that's four thematics to investigate and compare in the Australian context:

I'll investigate and illustrate three of Corrigan's four thematic groups.

main characters are acted upon, not active agents

characters identify with their means of transport

male escapist fantasy linking masculinity to technology

To invoke said Australian context: instead of a lecture written by me, I'm going to ask you this week to read a paper written by three people who at the time of writing were PhD students at Murdoch, and who have gone on to successful careers elsewhere in the academy: Rama Venkatasawmy, Catherine Simpson & Tanja Visosevic. The paper has the elaborate title 'From sand to bitumen, from bushrangers to "bogans" and "mongrels": the Australian road movie' and it was published in the Journal of Australian Studies, no. 70, 2001, 'Romancing the Nation', ed. Richard Nile.

I've asked the Library to make a copy of the paper from the journal and you'll find that (deo volente) in the eReader in the form of a PDF.

One of the points made early on by Venkatasawmy et al. is one about the essential practical difference between the American and the Australian road movie, namely, that you can't leave this country by road. Whereas the characters on American cinematic roads are often heard to be talking about getting to Mexico, or maybe Canada, the most that you can do in the Australian version is to get to or from the Big Smoke - or, in some cases, cross the country, say from Sydney or Melbourne to Perth. There are a couple of examples of films in which characters do just that.

Venkatasawmy et al. make the point that the road movie is part of a classic narrative form: the idea of an "archetypal journey as a metaphor for life itself." Many of you will have done MED116 Intro to Screen and will have encountered this idea, and also the idea that the journey is typically triggered either by a quest or by a desire to escape - and sometimes both. So Jason goes in search of the Golden Fleece, and medieval knights quest for the Holy Grail.

There is a precursor of the road movie, set in Australia, which differs from the archetype in the absence of what Corrigan requires as the only two defining characteristics: a vehicle nd a road. In addition, these are films in which the primary goal of the action, rather than a destination for the human beings involved, is the movement of domestic animals and their arrival at the end of the journey. I'm thinking of The Overlanders (Harry Watt, 1946) and The Sundowners (Fred Zinnemann, 1960).

These Australian so-called "classics" belong more to the western, and, as such, stem from a tradition of American droving movies (John Wayne was in at least one). Note that neither of these films is an "Australian" production, in the sense of finance and production company or studio. Although both were of course shot here, Harry Watt was working for Ealing (UK), and Fred Zinnemann for Warner Bros (USA).

Other Australian variants of the road movie occurs either when there is no road, or when the characters mostly walk. In The Back of Beyond (John Heyer, 1954, doco, 66 min.), for example, mailman Tom Kruse drives his truck through the sand from Maree to Birdsville, along the Birdsville Track. And in Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971), two English children (Jenny Agutter and the director's son) survive in the outback with the help of an Aboriginal boy (David Gulpilil). All three are literally on walk about. Burke and Wills (Graeme Clifford, 1985) also end up on foot. The explorers starve to death among food which they cannot recognise as such and Aboriginals who cannot understand why. Although the two young people in Beneath Clouds (Ivan Sen, 2002) spend some time in cars, they also spend a lot of the film simply walking by the side of the road, while the children in Rabbit-Proof Fence (Phil Noyce, 2001) don't even have roads to walk on.

Another kind of Australian road movie is one in which the characters drive, but don't really get anywhere, in films such as The Cars That Ate Paris (Peter Weir, 1974), The FJ Holden (Michael Thornhill, 1977), and Running on Empty (John Clark, 1982).

Driving

Driving

Let's return to the second point from Corrigan (via Cohan & Hark):

characters identify with their means of transport.

How about this for bonding with your vehicle:

Clip from The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994) 51"

Clip from Running on Empty (John Clark, 1982) 1'43"

Now for the first point taken from Corrigan:

main characters are acted upon, not active agents.

Clip from Doing Time For Patsy Cline (Chris Kennedy, 1997)

Clip from Welcome to Woop Woop (Stephan Elliott, 1997) 2'17" @ 19'55"

And to illustrate the third of the Corrigan ideas:

male escapist fantasy linking masculinity to technology,

I'll show a clip from Roadgames (Richard Franklin, 1981): a bit of comic relief, although from a mostly serious film. This is a thriller very much in the Hitchcock tradition. Franklin is a graduate of the film school at USC, the University of Southern California, and actually formally "observed" Alfred Hitchcock working on one of his films - which is as near as anyone got to being taught by the master. But it's also definitely a road movie. Franklin's latest movie, Visitors (Richard Franklin, 2003), is also a Hitch-type thriller, so some extent.

This is one of the handful of films which I find, as a native Western Australian, of particular interest, in that the characters' destination is Perth. Nikki and Al, from Kiss or Kill, are last seen in the sandhills of the WA south coast in the Margaret River area. The four fugitives in True Love and Chaos are heading for Perth from Melbourne; in fact Hugo Weaving's character is seen off from Perth airport by Miranda Otto's. Toni Collette's character Sandy (in Japanese Story) is also last seen at the very same airport, as she watches the plane taxi away carrying the other principal character, Tachibana Hiromitsu (Gotaro Tsunashima). And the boys in Thunderstruck (Darren Ashton, 2003) have to get to Bon Scott's grave in Fremantle Cemetery.

The ending of Roadgames is set in Perth, although not shot there: it's quite obvious if you know either Perth or Melbourne or both. However, the truck does arrive in Perth (a sign near the end says so: "PERTH 40"), and we do see the night lights of the city as the truck comes down Greenmount Hill. There are also a couple of other shots which Richard Franklin (on the DVD audio commentary) assures us are shot in outer suburbs of Perth, though, as he himself says, it's impossible to tell, as they are shot at night, and all you can see is the truck and the odd building.

But that's not what I'm going to show you. Here are a few moments from Roadgames. You need to know that the bad guy is in the dark green van, and the good guy is driving the semi-trailer truck. Which, by the way, reverses the situation in Steven Spielberg's classic road movie Duel (1971) in which Dennis Weaver is the hero in the car, and the truck itself is the villain!

Clip from Roadgames (Richard Franklin, 1981) 3'

Richard Franklin says he's proud of that shot in which Stacy Keach's truck pulls up in front of Jamie Lee Curtis. Cinematographers among you might have noticed that the truck pulls out to allow space for the camera to dolly around to face the then 21-year-old and not-yet-very-famous actress.

Perth is also the destination both for the characters in the film Kiss or Kill, and for the odd group in True Love and Chaos (Stavros Andonis Efthymiou, 1996).

Clip from Kiss or Kill (Bill Bennett, 1997)

Nikki goes through Zipper Doyle's wallet, distributing most of the contents, and then the wallet itself, by the roadside. The shot used is a typical shot, from the limited vocabulary available. This one is the "out-the-window" shot, which gives the feeling of movement, the force of the air, and, most importantly, the landscape in which the action is taking place: the empty Nullarbor.

Al (Matt Day) and Nikki (Frances O'Connor) are heading west across the Nullabor, not only to get away from their eastern past, but also to get away from their pursuers: both the bad guy, Zipper Doyle (Barry Langrishe), and the cops, the ubiquitous Chris Haywood and the sensitive Andrew S. Gilbert. Although Al and Nikki leave a trail of dead bodies, the script still manages to contrive a happy ending for them, leaving them at their beach shack, where they live happily at least until the last frame.

And in another recent film featuring the outback, Doing Time For Patsy Cline (Chris Kennedy, 1997), the same actress (Miranda Otto) provides the love interest (as Patsy Cline) for both male characters (Richard Roxburgh and Matt Day) on a road journey interrupted by doing time in the clink.

These three films have in common a journey along the long straight roads of the Australian interior (although in the last case the ultimate destination is out of the country, in Nashville, Tennessee). They may therefore be seen in that light as continuing a trajectory that goes back through The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994), Wrong Side of the Road (Ned Lander, 1981), Roadgames (Richard Franklin, 1981), the Mad Max trilogy (or at least the first two), and Backroads (Phillip Noyce, 1977).

Clip from Backroads (Phillip Noyce, 1977)

What they also have in common is that generically, as road movies, they are not significantly different from the Hollywood product, although of course they have Australian inflections and differ markedly in other respects. In the case of Backroads, Gary Foley was encouraged to improvise most of his dialogue, and he was very keen to represent life as it is really lived by Aboriginal people, including deciding how the film should end: with the death of his own character from a police bullet.

A different kind of "Australian inflection" of increasing interest is the development of situations in which foreigners are plunged in the Australian road + outback environment to see what happens. And it's quite striking that no fewer than three such recent films take an unsuspecting Japanese person and throw them in to see if they sink or swim.

Clara Law was most recently in the news with her documentary Letters to Ali (Clara Law & Eddie Fong, 2004). But a few years earlier she directed a striking film, beautifully shot by Dion Beebe (who won the Oscar for cinematography in 2006), called The Goddess of 1967 (Clara Law, 2000). I can't show you a clip from this, unfortunately - as I know exactly the moment I would screen - so I'll move on to a lesser film, but one with some similarities: Heaven's Burning (Craig Lahiff, 1997, script by playwright Louis Nowra). The Japanese girl in this film, Midori (Youki Kudoh) [isn't that a drink?!] is forced into the environment by being taken as a hostage by some incompetent bank-robbers, including Colin (Russell Crowe). Even worse, Rusty finds he has a soft spot for her ... which ultimately results in both both of them being killed in the manner anticipated by the film's title.

The clip shows one of the more unexpected encounters that one can have in the outback.

Clip from Heaven's Burning

On to a much better film, this time with a Japanese man getting himself in trouble with a tough Aussie sheila.

Clip from Japanese Story (Sue Brooks, 2003)

I might have finished - but we won't get this far - by bringing us both up to date and back home, with the guys from Thunderstruck (Darren Ashton, 2003), who we see firstly leaving a fairly recognisable city and then on their way to ... Fremantle Cemetery.

No clip from Thunderstruck (Darren Ashton, 2003)

The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

Cook, Pam & Mieke Bernink eds 1999, The Cinema Book, second edition, BFI, London.

Corrigan, Timothy 1991, A Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture after Vietnam, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

Dargis, Manohla 1991, 'Roads to freedom', Sight and Sound, 1, 3, July.

Dowell, Pat, 'The impotence of women', Cineaste, 18, 4.

Falconer, Delia 1997, 'We don't need to know the way home: the disappearance of the road in the Mad Max trilogy', in Steven Cohan & Ina Rae Hark eds, The Road Movie Book, Routledge, London and New York: 249-270.

Neale, Steve 2000, Genre and Hollywood, Routledge, London & New York.

Orr, John 1993, "Commodified Demons II: The Automobile", Cinema and Modernity, Polity, Cambridge: 127-154.

Robertson, Pamela 1997, 'Home and away: friends of Dorothy on the road in Oz', in Steven Cohan & Ina Rae Hark eds, The Road Movie Book, Routledge, London and New York: 271-286.

Taubin, Amy 1991, 'Ridley Scott's Roadwork', Sight and Sound, 1, 3, July.

The Wild One (Laszlo Benedek, 1954)

Route 66 (TV) (1960s)

Tom Jones (Tony Richardson, 1963)

Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)

Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969)

Duel (Steven Spielberg, 1971) (TV)

Vanishing Point (Richard C. Sarafian, 1971)

Two-Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 1971)

Kings of the Road (Wim Wenders, 1975) aka Im Lauf der Zeit

Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984)

Wild at Heart (David Lynch, 1990)

Thelma & Louise (Ridley Scott, 1991)

Highway 61 (Bruce McDonald, 1991) (about taking a corpse to New Orleans)

Garry Gillard | New: 27 September, 2004 | Now: 25 December, 2023