Sunday too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975)

Sunday too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975)

This was the presentation in the second week in 2006.

Tom O'Regan 1996, 'Unity', Chapter 8 of Australian National Cinema, Routledge, London: 189-212.

Ian Craven 2001, Introduction: 'Australian Cinema Towards the Millennium', Australian Cinema in the 1990s, Portland, London.

Nigel Spence & Leah McGirr 2001, 'Unhappy endings: the heterosexual dynamic in Australian film', in Ian Craven ed., Australian Cinema in the 1990s, Portland, London: 37-56.

Jonathan Rayner 2000, 'Introduction', Contemporary Australian Cinema: An Introduction, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Clips

Sunday Too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975)

Proof (Jocelyn Moorhouse, 1991)

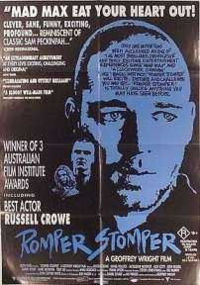

Romper Stomper (Geoffrey Wright, 1992)

Silent Partner (Alkinos Tsilimidos, 2001)

Don's Party (Bruce Beresford, 1976)

He Died with a Felafel in His Hand (Richard Lowenstein, 2001)

Main screening

Muriel's Wedding (P. J. Hogan, 1994) 100 min. (By the way, this film was badly done for the Oz Film Database [your second assignment]: I'd be glad if someone volunteered to take it on and do a much better job to replace the one that's there.)

In 2004-5, this week was concerned with the "western". The chapter on the western is available, as is the related presentation, and you can choose this topic for your first essay if you wish. Of course, you would now take account of The Proposition (John Hillcoat, 2005).

Here's a quotation which sums up, if not the project of this whole unit, at least the focus of the inquiry of this week.

... the concern is with what the films are about. Do they share a common style or world view? Do they share common theses, motifs or preoccupations? How do they project the national character? How do they dramatise the fantasies of national identity? Are they concerned with questions of nationhood? What role do they play in constructing the sense or the image of a nation? One of the most productive ways of exploring national cinema from this perspective is in terms of genre analysis, for the processes of repetition and reiteration which constitute a genre can be highly productive in sustaining a cultural identity. Andrew Higson 1995, Waving the Flag: Constructing a National Cinema in Britain, Clarendon, Oxford; as cited in Rayner, Jonathan 2000, Contemporary Australian Cinema: An Introduction, Manchester University Press, Manchester: 21-22.

Today I am going to draw on Tom O'Regan's work on the notion of unity in Australian cinema (it is, of course, one of the most important issues in the book as a whole) - as in this statement of intention from early in his 1996 book.

... Australian cinema ... appears as a genre or type of dominant film-making or as so many thematic regularities - a masculinist cinema hypercritical of family life and male-female relationships which eschews conventional heterosexual romance structures and Oedipal trajectories. Critics and film-makers also unify Australian cinema around particular stylistic preoccupations - in particular naturalism - and around cultural and stylistic preoccupations with settings and landscape. (O'Regan 1996: 7)

and as elsewhere in this variation on the same group of ideas:

Talking of Australian cinema's national specificities, considering Australian cinema as a genre, elucidating its narrative, thematic and stylistic preoccupations and generalizing about its uses of setting, light and landscape produce a sense of its regularity, unity and convergence. (1996: 189)

In dealing with these thematic preoccupations - which is of most relevance to this unit which looks at Australian film in terms of genres and types - O'Regan suggests this:

A related way of disclosing the unity of Australian cinema acknowledges differences among films but looks to larger regularities of theme, plot and representation for a sense of unity. This process enables critics and film-makers alike to create connections between projects that would otherwise be kept separate. They give a fragmented industry and production context a semblance of coherence. So it is possible to assemble the thematic concerns of Australian cinema in its emphasis upon ordinariness, its male predominance, its eschewing of heterosexual romance; its highlighting of father/daughter, mother/daughter relations with their unusual Oedipal concerns. (1996: 198)

I'll take up some of these points and try to develop and exemplify them.

Sunday too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975)

Sunday too Far Away (Ken Hannam, 1975)

I'll use a sequence which shows in three scenes both negative and positive aspects of Australian masculinity. In the first, one of the shearers, Berry [Beresford] (Sean Scully), is called a "queer" because - paradoxically - he is writing to his wife, instead of hanging around with the other blokes. This is clearly a moment in "a masculinist cinema hypercritical of family life and male-female relationships which eschews conventional heterosexual ... structures". When Berry reveals who he is writing to, another shearer reacts with: 'Bugger me!' - not with the literal meaning, presumably.

In the scene immediately following, the oldest shearer, Garth (Reg Lye), has died, and Foley (Jack Thompson) insists that his body be treated with the same respect that would have been afforded the cocky (the owner or manager of the sheep station). This illustrates the mateship which is an enduring quality of the Australian male. It also shows the Australian resistance to the markers of class division.

Another scene shows the hero, Foley, the hard man, talking about his childhood in the orphanage, and then when he was 20 being bought a beer as a mark of respect by the toughest guy in the toughest pub. He then bursts into tears, perhaps because of the presence of a woman, or perhaps because of Garth's death, predicting his own, and despite the fact that he has just been talking about being tough - showing the vulnerability underneath the gun shearer's rugged exterior. The scene is remarkable for the way in which the woman is almost entirely ignored. This is indeed an example of "male-female relationships which eschews conventional heterosexual romance structures".

Ken Hannam, the director, unfortunately died in 2004, so there will never be a director's cut of the film, which was vandalised by producer/distributor bastardry. You may wonder about the isolated, bizarre and unmotivated scene between Foley and the cocky's daughter (Lisa Peers) with the generic name Sheila, the result of savage cuts. [clip "queer" 1.09.26 - 1.14.36]

(If you watch it on the 2001 DVD you may also find some of the dialogue incomprehensible, especially in the shearing shed when the sound of the machinery drowns it out. This is an important film which I would show first in this unit if I had a good print from a good cut - which will almost certainly never be possible. I showed it in the second week in 2002, but it was understandably not well received.)

Proof (Jocelyn Moorhouse, 1991)

Proof (Jocelyn Moorhouse, 1991)

Proof is a film about a blind man who takes photographs. As he cannot see them he needs someone whom he can trust to describe the photos to him. Martin (Hugo Weaving) has known Celia (Genevieve Picot), his housekeeper, for some time, but he does not trust her. He meets Andy (Russell Crowe), asks him to describe his photographs, and their relationship becomes the central one in the film.

In the sequence I'll show, Celia has seduced Andy, and they are discovered by Martin in his own bedroom. In the scene which follows, Celia's motivation becomes clear. ... But the film ends with Celia literally out of the picture and Martin and Andy continuing to be friends.

Barbara Creed observes:

Australian films frequently - and perversely - tend to construct the 'normal' heterosexual couple as in excess. Marginalization of the couple is accompanied by the general failure of Australian films to deal convincingly with encounters between the heterosexual couple which are sexually charged and erotically powerful. (Creed 1992: 22)

Creed's analysis of Moorhouse's Proof suggests that while it

... is not about a homosexual relationship its exploration of male bonding, based as it is on the exclusion of woman, suggests that all relationships between men involve a degree of homoeroticism. Woman is represented as an abject figure who must be located outside the territory of the male couple. (Creed 1992: 16; as quoted by O'Regan 1996: 199)

In plain terms, the woman is (literally) pushed away, despite her attempt to come between the men. She wants to be the one who is trusted, but Martin trusts only Andy - despite his betrayal of that trust! [clip "discovery" 1.10.10 - 1.14.37]

Romper Stomper (Geoffrey Wright, 1992)

Romper Stomper (Geoffrey Wright, 1992)

Romper Stomper has another odd group of three. In the final scene of the film, Hando (Russel Crowe) is persuading Davey (Daniel Pollock) to drop Gabe (Jacqueline McKenzie). She hears this and sets fire to the car so that they cannot continue. She tells Davey that he is useless without Hando, but also that it was she who reported the gangs' whereabouts to the police. Hando tries to kill her, and in desperation Davey is eventually forced to kill Hando.

The relationship between Hando and Davey is not homosexual, but it is a profound bond, ultimately broken not so much simply by the intervention of Gabe as by the tragic flaw in Hando's nature, that he is obsessively uncompromising to the point of killing whatever it is in his way, including his former lover but now "abject" Gabe.

Tom O'Regan points out that "The film exacts a cunning reversal; Davey, not Gabe, is the object of exchange, the object in circulation, in this love triangle. He circulates between the two strong characters." (1996: 151) [clip "revelation" 1.18.38 - 1.26.00]

Silent Partner (Alkinos Tsilimidos, 2001)

Silent Partner (Alkinos Tsilimidos, 2001)

For a less serious look at a close (and also not homosexual) relationship between two men, let's look at a film about a couple of losers. There is actually a film called Dags (Murray Fahey, 1998), which I find it unbearable; but I think we should include a look at some dags this week: some very ordinary Aussies. Here are John and Bill (David Field and Syd Brisbane); Silent Partner is the name of their dog, which dies when they "dope" it: inject it with a drug to make it run faster.

(Alkinos Tsilimidos seems to specialise in directing films about losers: Man of Straw is a documentary about a week in the life of a compulsive gambler; Every Night ... Every Night (1994) is about people getting beaten up regularly in prison; and Tom White (2004) is about a man (Colin Friels) who to some extent voluntarily leaves his family and job to become a homeless person.)

The conversation begins with why Bill was going to see Silver - a more powerful man - but the subject soon turns to 'loyalty' and 'betrayal'. Trust is once again the key to a relationship, as it was in Proof. The 'needle' they're talking about is the one they used to dope - and kill - the dog. Bill has been thinking about using it on himself, that is, to commit suicide. In this second-last scene of the film, the two old friends look as though they are finally going to break up - because, as Bill tells John, when he's with him he feels lonely: a nice paradox. [clip "lonely" 1.08.03 - 1.15.54]

Don's Party (Bruce Beresford, 1976)

Don's Party (Bruce Beresford, 1976)

I've chosen comedies to finish today's presentation, beginning with one of the more mature films from the second half of the 1970s. Once it was established that we did have a film industry in Australia, and once we'd got over the excitement of the making the ocker comedy and sexploitation films of the early 1970s, it was possible to take a look at ordinary middle-class Australians at play.

Pike & Cooper tell us this about Don's Party.

On election day, 25 October 1969, Don [John Hargreaves] and Kath [Jeanie Drynan] throw a party to celebrate what they hope will be the first Labor Party victory in twenty years. The film is less about politics than about the people at the party: as the optimism of the Labor supporters degenerates into the bitterness of defeat, the party also degenerates into an early morning alcoholic haze and the painful exchange of home truths.

David Williamson's highly successful play was only marginally altered for the screen (by Williamson himself), although until shortly before production began it had been intended to re-set the film in December 1975 at the time of the Whitlam-Fraser electoral contest. Attempts to 'open up' the action were also abandoned in the final screenplay, and although off-stage bedroom scenes now appeared on-screen, and a new scene was added of a nude swim in a neighbour's backyard pool, the bulk of the film was set resolutely inside Don's house to sustain the tensions and claustrophobia of the party.

In this sequence, the angry dentist has had an argument with his wife and left the party, but he changes his mind and returns to find her in bed with another man. Not a very successful marriage, apparently. [clip "coitus interruptus " 49.42 - 54.33]

He Died with a Felafel in His Hand (Richard Lowenstein, 2001)

He Died with a Felafel in His Hand (Richard Lowenstein, 2001)

After that dismal business, let's abandon the theme for today and simply move on to a big finish. As you may know, one of the things I love about some Australian films is the insane risk-taking which can sometimes be involved, as in Welcome to Woop Woop (Stephan Elliott, 1997). I'll show my favourite scene from Richard Lowenstein's indescribable film, He Died with a Felafel in His Hand. As the Flipster says, "Woah! Freak show, dude!" (He's the one who dies with a felafel in his hand in the title scene.) [clip "napalm" 37.43 - 43.33]

Creed, Barbara 1992, 'Mothers and lovers: Oedipal transgressions in recent Australian cinema', Metro, 91: 14-22.

Gibson, Ross 1992, 'The nature of a nation: landscape in Australian feature films', in South of the West, University of Indiana Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis: 63-81.

Pike, Andrew & Ross Cooper 1998, Australian Film 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, revised edition, Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

Ryan, Tom 1980, 'Historical films', in Scott Murray ed., The New Australian Cinema, Nelson/Cinema Papers, Melbourne: 113-31.

Turner, Graeme 1989, 'Art directing history: the period film', in Tom O'Regan and Albert Moran eds, The Australian Screen, Penguin, Ringwood, Vic.: 99-117.

Garry Gillard | New: 9 May, 2004 | Now: 28 April, 2022