This week's readings | Australasian women's films

See also: melodrama

maternal melodrama

Radiance (Rachel Perkins, 1999)

love story

Better Than Sex (Jonathan Teplitzky, 2000)

Love and Other Catastrophes (Emma-Kate Croghan, 1996)

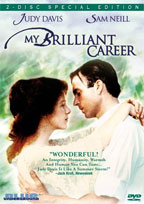

My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979)

medical discourse film

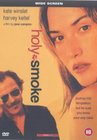

Holy Smoke (Jane Campion, 2000)

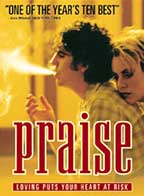

Praise (John Curran, 1999)

paranoid gothic thriller

The Piano (Jane Campion, 1983)

Perfect Strangers (Gaylene Preston, 2003)

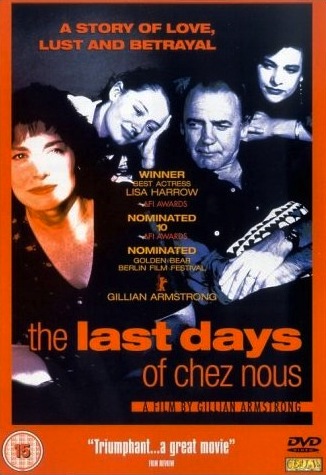

The Last Days of Chez Nous (Gillian Armstrong, 1992) 96 min.

My plan in this week is simply to take on board Mary Ann Doane and Jeanine Basinger's three-point definition of the "woman's film". (For references see the chapter for the week.) They suggest that the genre is defined by:

the centrality of its female protagonist

its attempt to deal with issues deemed important to women

its address to a female audience

Basinger's straightforward "working definition" simply states that:

A woman's film is a movie that places at the center of its universe a female who is trying to deal with emotional, social, and psychological problems that are specifically connected to the fact that she is a woman.

Doane identifies these sub-categories in 1940s Hollywood films:

maternal melodrama (focusing on a mother's joys and tribulations)

love story (concentrating on the vicissitudes of heterosexual romance)

medical discourse film (with its focus on a physically or mentally ill woman)

paranoid gothic thriller (centred on a wife's fear of her husband's possibly murderous designs on her)

Let's see if these sub-genres have any application to Australian features.

In the now-defunct melodrama presentation I showed clips from Way Down East (D. W. Griffith, 1920, with Lillian Gish) and Caddie (Donald Crombie, 1976), in the context of melodrama, but both films definitely also focus on a mother's joys and tribulations - mostly the latter. And so does High Tide (Gillian Armstrong, 1987) - in which there are not one but two mothers.

In the week on social problem films, I showed a clip from Teesh and Trude (Melanie Rodriga, 2002) which centred on the custody of the women's children. Although Kate, in Angel Baby (Michael Rymer, 1995) never actually becomes a mother - because she dies in childbirth - a significant portion of the film is concerned with the conception and gestation of the child, Astral; and her pregnancy drives a lot of the actions of her and her partner, Harry. And in Rabbit-Proof Fence (Phillip Noyce, 2001), although the emphasis is on the experiences of the children, we are well aware of the suffering of their mothers.

My example this week will unfortunately have to involve a gigantic spoiler - but without it you won't see the point of the motherhood issue at all. Radiance (Rachel Perkins, 1999) looks like a meeting of three sisters after the death of their mother, and some of the action is taken up with the youngest sister, Nona (Deborah Mailman) discussing the father she believes is Aboriginal. To quote from the website contributed to by students of this unit:

Nona exists in a state of delusion concerning her father - believing him to be the 'Black Prince' - the one true love of her mother's life, a dark and handsome rodeo rider. She is continually searching for signs of his past presence within the home and is persistent in her ignorance towards her sister's obviously negative and secretive responses.

Louisa Davin continues:

... the ... climax comes with the house already in flames. Breaking at Nona's continual reference to the 'Black Prince,' Cressy exposes the truth of Nona's existence. She is in fact the daughter of Cressy, who was raped by one of her mother's boyfriends under the house at age twelve. (Louisa Davin, 'Radiance')

This recalls the situation in High Tide - but this is much more intense. Cressy (Rachael Maza) and Mae (Trisha Morton-Thomas) have always pretended that Nona (Deborah Mailman) is Cressy's younger sister. Imagine Cressy's feelings over the years and now, at the time of the revelation!

At least one of the older women is of the Stolen Generation, having been taken from her mother. Nona's story is a metaphor for that: she too has not had the relationship with her actual natural mother that she should have, having been deprived at conception of that possibility.

Radiance (Rachel Perkins, 1999). The clip shows the climax, with the house burning down, and the revelation.

[clip "fire" 1.06.51 - 1.11.32 (house crumbles)]

Better Than Sex (Jonathan Teplitzky, 2000)

Better Than Sex (Jonathan Teplitzky, 2000)

Clip from the beginning: the characters themselves discuss their situation, to camera, needing no comment from me. The recognisable actors are David Wenham and Susie Porter. The cab driver is the veteran Kris McQuade, who was the first topless girl in

Alvin Purple, as long ago as 1973 (Tim Burstall).

[clip "sex" 2.22 - 6.25 here we go again]

Love and Other Catastrophes (Emma-Kate Croghan, 1996)

Love and Other Catastrophes (Emma-Kate Croghan, 1996)

There's no reason why, in the noughties of the new millennium, that this category can't be extended to include homosexual romance. We've already mentioned this between males; in this film it's between females.

In this scene, Danni (Radha Mitchell) and her new girl-friend Sevita (Suzi Dougherty) come upon Mia (Frances O'Connor) decompensating in the grounds of Melbourne University. Mia takes her revenge on Danni with her revelations. Sevita does not speak during the whole film, by the way. Noted teacher and writer on film Adrian Martin plays himself, but is not in this scene. (This was before Radha Mitchell and Frances O'Connor got famous.)

[clip "farm" 44:32 - 47.0 key]

My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979)

My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979)

As more films are released on disk, we have more presentations of the vicissitudes of heterosexual romance to choose from. Here's an example from the first decade of the Renaissance (of Australian cinema), one of the "quality", or "AFC genre" films, of which we can be "proud". It's best-known now as the film which launched the brilliant careers of both Judy Davis* and Sam Neill, but it's also important for continuing the brilliant career of the woman novelist who wrote the book of the same name, Miles Franklin (who wrote under a male pseudonym so that she could get published).

(*Judy Davis had previously appeared, without attracting much attention, in High Rolling (Igor Auzins, 1977) as a hitch-hiker, a character perhaps recalled in Jamie Lee Curtis's similar appearance in Roadgames, Richard Franklin, 1981. Davis was born 23 April 1955, Perth, Western Australia.)

In these two clips, Sybylla Melvyn (Judy Davis) rejects the advances of Harry Beecham (Sam Neill) and then Frank Hawden (Robert Grubb), as her writing career is more important to her than sex or marriage.

[clip "advance" 23.53 - 25:15 - Syb off screen]

[clip "proposal" 31.47 - 32.47 - Frank leaves, and the sheep provide authorial commentary]

Holy Smoke (Jane Campion, 2000) features an allegedly mentally-disturbed woman, Ruth (played by the outstanding Kate Winslet).

Holy Smoke (Jane Campion, 2000) features an allegedly mentally-disturbed woman, Ruth (played by the outstanding Kate Winslet).

In the clip, PJ (Harvey Keitel), who comes into the narrative identified as a "cult exiter", speaks of Ruth as a "client", so she is already in a subaltern (relatively disempowered) category. She has to go through a sort-of "three steps" program to be freed from her supposed possession by her Indian guru, Baba.

[clip "PJ" 20.40 - 22:44 to Sophie Lee's pre-submission]

Angel Baby fits here again: it seems to be every kind of woman's film, as well as a melodrama and a social problem film with art film moments! Another such wide-ranging film is Lilian's Story.

Angel Baby fits here again: it seems to be every kind of woman's film, as well as a melodrama and a social problem film with art film moments! Another such wide-ranging film is Lilian's Story.

The clip I showed from Angel Baby in the social problem presentation is the case conference with a coupla shrinks, the expectant parents (Harry and Kate), and his brother and wife. Harry (John Lynch) and Kate (Jacqueline McKenzie) have a very strong sense of what they want, although they don't express themselves in what everyone might think are conventional terms, but the doctors have their jargon and prejudices to rely on. I won't show it again, but hope you recall it.

[clip "shrink" 38.10 - 40:48 message from God]

Praise (John Curran, 1999)

Praise (John Curran, 1999)

The narrative as a whole starts and finishes with Gordon (it's from a novel written by a man, Andrew McGahan), but Sacha Horler's female character, Cynthia, is much more interesting, and more central, in the sense that not only she is much more energetic, but also that she motivates almost everything Gordon does. Cynthia's body is in the forefront of the story. Not only does she have the problems already mentioned, she also likes fucking to the point where it is almost a disorder: it is discussed in those terms by the characters.

Two clips. In the first, Gordon (Peter Fenton) scratches the eczema on the back of Cynthia (Sacha Horler).

[clip "eczema" 37.00 - 38:10 - hideous/wedding]

In the second, Cynthia has found that she is pregnant, and that she (they?) have genital warts.

[clip "warts" 53.14 - 54:54 - starts car)

In the Cut (Jane Campion, 2003) could be argued to belong to this group, despite the technicality of Meg Ryan's character not actually being married to Mark Ruffalo's - but it is not an Australian film in any sense.

I wish I could show you a clip from To Have and To Hold (John Hillcoat, 1997), Hillcoat's weird film about a woman who marries an, um, unusual man who takes her to Papua New Guinea, and ... well, you have to see it! It's a perfect example of this sub-genre. Rachel Griffith is amazing, as usual, playing opposite the very strange Tcheky Karyo. Hillcoat later directed The Proposition (2005).

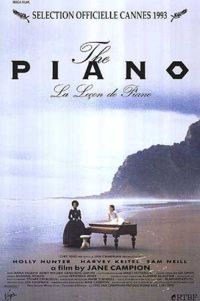

The Piano (Jane Campion, 1983)

The Piano (Jane Campion, 1983)

As I can't come up with a single other example, and I don't have a copy of To Have and To Hold, and as this seems to be Jane Campion week (not surprisingly), I'll show you a clip from The Piano (Jane Campion, 1983), from near the end of the story.

Ada McGrath (Holly Hunter) has been sent to New Zealand by her father to marry Alasdair Stewart (Sam Neill). Her father told her to "be silent": and so she has remained since she was a child - which puts her in the previous category of "mentally ill woman". She falls in love with George Baines (Harvey Keitel), and Stewart spies on their love-making. He himself tries to make love to Ada, but he lacks Baines's commitment and sensitivity - he tries at first to rape her ... and then rejects her sensual advances. Finally, he falls back on outright physical violence to make his point, by cutting off hers, as it were. Different people will see the act differently, but I see it now as partly a punishment, but mostly as evidence of Stewart's need to be in control. The index finger is a handy symbol for lotsa things, which I hope we won't have to discuss in tutorials; I think it's enough to note that Ada needs it to play the piano.

The clip begins with Ada's daughter disclosing to her new Papa, Stewart, that her mother is having an affair with Baines. Stewart reacts violently, cutting off one of Ada's index fingers.

[clip "axe" 1.30.49 - 1.35.34]

In Perfect Strangers (Gaylene Preston, 2003) a man (Sam Neill) abducts a woman (Rachael Blake) apparently in order to seduce her - even though it seems they have only just met. He soon begins to act in a threatening way. It's a weird movie. This scene shares some of its music with the scene from Radiance.

[clip "bath" 16.15 - 20.24]

The Last Days of Chez Nous (Gillian Armstrong, 1992) is one of my favourite films. It's written by Helen Garner and directed by Gillian Armstrong, so what it has to say for women is of more than usual importance. "Chez nous", by the way is French (JP is French) for "our place", so the title could mean something like "The last days when we were all together", or "The last days of 'Our Place'". Like much of Garner's work, the script is based on her own life and people she knew. She herself was married to a Frenchman, and he did leave Helen for her sister - as in the film.

Garry Gillard 2002, 'Perspectives on Radiance', Australian Screen Education, 29: 179-182.

Ceridwen Spark, 'Reading Radiance: the politics of a good story', Australian Screen Education, 32, Spring, 2003: 100-104.

Garry Gillard & Lois Achimovich, 'The representation of madness in some Australian films', Journal of Critical Psychology Counselling and Psychotherapy, 3, 1, Spring 2003: 9-19.

The presentation in 2006 was to have come from Helena Sharp, but she was unavailable. Serenades (Mojgan Khadem, 2001) was her choice of main screening. I would like to have shown The Last Days of Chez Nous (Gillian Armstrong, 1992), but only have the videotape copy which is all that's available as yet.

Garry Gillard | New: 28 March, 2004 | Now: 28 April, 2022