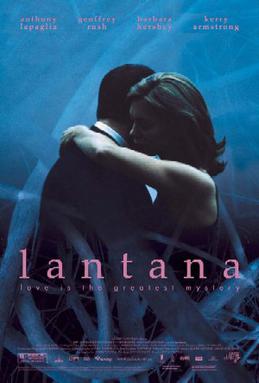

Lantana (Ray Lawrence, 2001) wr. Andrew Bovell (play and screenplay), prod. Jan Chapman; Anthony LaPaglia, Geoffrey Rush, Barbara Hershey, Kerry Armstrong, Rachael Blake, Vince Colosimo, Russell Dykstra, Daniella Farinacci, Peter Phelps, Leah Purcell, Glenn Robbins, 115 min.; AFI 2001: best picture, direction, actor, actress ...

One of the best films ever written in Australia, this one allows an insight into half a dozen relationships of different kinds.

In Lantana (Ray Lawrence, 2001) there are no fewer than six couples under examination. Leon Zat (Anthony LaPaglia) and his wife Sonja (Kerry Armstrong) are the most significant. Leon is a policeman who is shown to be occasionally more violent than is required, not only with criminal suspects, but also to some extent with his own two sons, though they appear to be perfectly pleasant adolescents. He seems to be going through some kind of midlife crisis: he runs to keep fit, although he appears to have a heart condition, and he has started an affair with Jane O’May (Rachael Blake), who is estranged from her husband Pete (Glenn Robbins). Sonja is seeing psychologist Valerie Somers (Barbara Hershey), who is married to academic John Knox (Geoffrey Rush). Their only child Eleanor has been killed in an unsolved crime, and Valerie has written a book about all this with the child’s name as the title. John is slightly mysterious, as the plot requires, seems unable to recover from Eleanor’s death—unlike Valerie—and may also be in a crisis of midlife. So their marriage is far from blissful. A contrast to these three dysfunctional relationships is provided by the couple who live next door to Jane: Nik and Paula Daniels (Vince Colosimo and Daniella Farinacci). In a somewhat clichéd way, class enters the equation, as they are happy with their messy, sexy life, even though they seem to be less well-off than the other couples. Their happiness is radically changed when Nik is suspected of having killed Valerie.

There are another two couples who would normally be regarded as being peripheral to the main business of this film, but who are pertinent for my purposes in that they represent an extension of the range of possibilities of proto-families. Another of Valerie’s clients is Patrick Phelan (Peter Phelps). He is gay and she feels that his attitude towards her is somewhat threatening, as she tells both her husband and her tape recorder. So he too becomes a suspect—after Valerie disappears and then is found dead—at which point Leon commandeers the tape. He subsequently forces his way into Patrick’s apartment, but instead of the lover he expects to discover, he finds a completely new character: Patrick’s (nameless) lover is played by Lani Tupu, who looks Polynesian or Maori (as the actor’s name also suggests). Perhaps partly because of this unpleasant incursion, it seems by the end of the film as though the lover has given up, not only on Patrick, but perhaps also on homosexuality, as we see him, from Patrick’s point of view across the street, with his wife and children in a restaurant. Patrick is standing in the rain, the water dripping down from his hood, like tears, in a conventional representation of the sorrow he is feeling. It is difficult not to interpret this scene as an affirmation of the heterosexual nuclear family: they are animated, warm, well-lit, while the lonely gay man watches helplessly in his exclusion.

The other proto-couple I see as providing a direct contrast with this one. Leon’s police colleague, Claudia (Leah Purcell), is hopeful of some sort of romantic possibility with an unnamed man. She is not confident, and there has been a setback, but at the denouement she is looking forward to their next meeting. One might wonder why she is in the story at all: to provide a collegial ear for Leon’s confession, perhaps, and also collegial judgement of his unnecessary force. And having been included, her character needs some filling out, and she so given this potential liaison. However, I see her situation, in a structural way, as providing one more position along a continuum of possibilities with regard to the formation and preservation of the family.

The plot concludes with this range of positions, from least to most positive. Pete and Jane’s marriage is over: she has had a disappointment with Leon and seems completely aimless; he is depressed and uncomprehending. John is of course alone, after the death of his wife; but he seems to have been generally alienated anyway. We last see him in his luxurious mountain eyrie, looking sullenly out over the vista, and we can only guess what he might be thinking about: suicide, perhaps. Patrick is also alone, but is not as old as John—and perhaps his commitment to his lover was not as long-term as John’s and Leon’s to their wives. Although he is miserable now, he may be happy again, which is much harder to imagine in John’s case. Jumping to the last position on the spectrum: as I’ve said, Claudia is hopeful of her new romance ... which leaves Leon and Sonja.

There are two final scenes which deal with the ambiguity of the ultimate (as far as the plot goes) situation in their relationship. In the first, Leon plays the tape of Sonja’s consultation with Valerie, from the point where he has left off previously. Valerie was then heard to ask if Sonja still loves Leon: he now listens to her answer. Sitting in his car, he sobs uncontrollably, in a moment of catharsis. The final scene of the film shows the couple dancing together. (Dancing has earlier been established as a motif for relational negotiation.) As there is nothing else in the frame, all that one can attend to is the position of the dancers and their expression—and Celia Cruz’s singing, I suppose. Their eyes are fixed on each other’s, whether evaluating or transacting. They dance slowly from the centre, first to one side of the frame and then over to the other, where the film concludes—and it’s noticeable that Leon is leaning slightly in towards Sonja, while she is leaning slightly away from him. The couple who are the most ambiguous—in terms of their future prospects—end up without any definite new commitment or separation—and with only this slightest of indications as to possible differences in their attitudes (literally) towards each other.

See also: chapter on melodrama in my Ten Types of Australian Film.

Wikipedia page

IMDb page

Garry Gillard | New: 24 September, 2012 | Now: 13 December, 2019