Australian Cinema > types > Indigenous Issues

List of 'indigenous' films | bibliography

Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976)

Journey out of Darkness (James Trainor, 1967)

Bitter Springs (Ralph Smart, 1950)

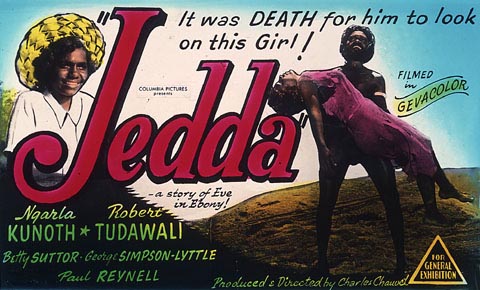

Jedda (Charles Chauvel, 1955)

Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971)

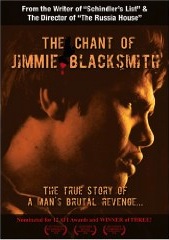

Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, The (Fred Schepisi, 1978)

Blackfellas (James Ricketson, 1993)

Jindabyne (Ray Lawrence, 2006)

Beneath Clouds (Ivan Sen, 2001)

When I was teaching Australian Cinema, because my approach was generic, I did not deal with certain issues in weekly lectures, but only as arising incidentally. One elephant in the room was always the representation of Aboriginal people. So I now offer this brief 'presentation' on Indigenous Issues. I cannot include relevant film clips myself, but fortunately the National Screen and Sound Archive has made available many relevant examples on their australian screen website. I have already put up a list of films with Indigenous themes.

As can be seen from my chronological list, Aboriginal characters appear in Australian films from the very beginning. The first feature, The Story of the Kelly Gang (Charles Tait, 1906) is without Indigenous representation, but it was only one year later that the black tracker Warrigal (played by a white actor in blackface) appears in Robbery under Arms (Charles McMahon, 1907; based on the novel by Rolf Boldrewood). A very large number of bushranger films were made in the next few years, culminating in 1911, when more feature films (on any subject) were made in Australia than in any other year. A large proportion of them concerned bushrangers, including, obviously, the Kellys, but also Dan Morgan, Captain Moonlite, John Vane, Thunderbolt, and so on. And some of these outlaws had a faithful Aboriginal companion. There are a number of possible reasons for this, all of which could be relevant. Such men may well historically have had the good fortune to gain an Aboriginal guide and assistant. Secondly, the faithful companion could have provided a striking plot point - as, by saving the life of the main character. And thirdly, he (or she) also represented the Noble Savage, an eighteenth-century figure who continued to exist even under colonialism. But it was not only in bushranger films that Aboriginal characters played key roles in the plot.

So, in Thunderbolt (John Gavin, 1910) John Gavin, as Thunderbolt, "is rescued from a police trap by a half-caste girl ..." (Pike & Cooper 1998: 11). And in another of Gavin's films, Assigned To His Wife (John Gavin, 1911) "in the dramatic highlight of the film, Jack's faithful Aboriginal friend, Yacka, contrives to rescue him with a 'Dive for Life' in which the Aboriginal boy dives 250 feet over a precipice into a river." (Pike & Cooper 1998: 27) In The Squatter's Son (E. J. Cole, 1911) "in a climactic horseback escape, the hero is helped by an obedient 'Black Boy' who destroys a bridge to delay the pursuers." (Pike & Cooper 1998: 17) In Moora Neya, or The Message of the Spear (Alfred Rolfe, 1911) "after 'a weird and fantastic' corroboree, the tribe departs to capture Harry, but one responsible tribesman, Budgerie, manages to alert the station men by writing a message on a spear: 'Blacks kill Harry tonight 30 Miles Hut, HELP!' The stockmen ride to the rescue and save Harry just as the Aborigines perform a 'Death Dance' around him." (Pike & Cooper 1998: 21)

Because only a handful of these early films exist, even in fragments, it's necessary to rely on the outstanding research of Pike and Cooper. Unfortunately, they don't reveal the part played in Dan Morgan (Spencer's Pictures, 1911) by Aboriginal characters, though Peter Malone tells us that there were "Aborigines associated with a bushranger" (Malone 1987: 3). I assume this is the same Morgan who is the subject of Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976), one of the two film roles that brought Dennis Hopper to Australia. Mad Dog has the great good fortune to team up with an Aboriginal companion played by David Gulpilil. And there is a clip from the film available from the australianscreen site, from the National Film and Sound Archive.

Mad Dog Morgan (Philippe Mora, 1976) David Gulpilil, Dennis Hopper. In this clip, Gulpilil's character Billy appears to be delighted to be caring for the injured outlaw (despite his being played by erratic and unreliable Hopper).

I've mentioned that the first appearance of an Aboriginal character was courtesy of a white actor in blackface, in only the third feature film made here. Unfortunately, the last instance of this shameful practice was as late as 1967.

Once again, there is a clip available from the australianscreen site, from the National Film and Sound Archive, which shows a scene from this film. It's actually part of the Darlene Johnson's great documentary, Gulpilil: One Red Blood. In the words of the Teachers' Notes from that page:

The clip concludes with footage from the 1967 film Journey Out of Darkness, in which two Indigenous characters are played by a white man in 'black face' and by Kandiah Kamalesvaran (Kamahl), who is of Sri Lankan descent.

Ed Devereaux in blackface in Journey out of Darkness (James Trainor, 1967) in front of a rock made up to look like Uluru to appear authentically Australian

Fortunately, it's not all bad news from the days before the Australian Film Renaissance (from 1970 onwards). Ralph Smart's 1950 film Bitter Springs is for its time quite an enlightened depiction of the conflicting claims on the land of the first inhabitants and the newcomers. The water source of the title is sold to a pioneer family as part of a parcel they buy from the government. But it is of course the property of the traditional owners, and conflict arises. The Aboriginal group lose the battle, but at least they have been shown to have some right to assert their claim on the waterhole. And at the end, there is an amazingly rapid deus ex machina ending, which when I first saw the film I found quite ridiculous. We see Chips Rafferty's character wishing that the locals would only understand what the country needs - lots of sheep - and then there's a cut to the 'future' with an Aboriginal shearer doing his thing. It's silly - but I'd like to think it's well-intentioned. But read Deb Verhoeven's article for a considered opinion.

Bitter Springs (Ralph Smart, 1950) Henry Murdoch, Bud Tingwell, Gordon Jackson (a Scot); the English comedian Tommy Trinder is also in it for no good reason. No clip available. I don't have any kind of copy of this film myself.

There's a giant leap forward in 1955, with the first appearance of a film with Aboriginal central characters, Jedda (Charles Chauvel, 1955).

Mudrooroo wrote approvingly about this film in 1987, in an article which is essential reading.

It is to Chauvel's credit, or perhaps in spite of Chauvel, that the only dignified Aboriginal male lead that has been allowed to exist in films made by white directors in Australia is in Jedda, and, though Marbuk does die in the end, it is because he has offended tribal law rather than because of anything the whiteman has shot at him. (Continuum, 1, 1)

However, a later critic, Marcia Langton, refuses to take this story at face value and expresses a much more complex and negative view.

Chauvel's Jedda (1955) expresses all those ambiguous emotions, fear and false theories which revolve in Western thought around the spectre of the 'primitive'. It rewrites Australian history so that the black rebel against white colonial rule is a rebel against the laws of his own society. (Langton 1993: 45)

This seems to me to be yet another case of a critic castigating an artwork for not being a different piece than the one it actually is. She wants the Chauvels to have made a different film from the one they did actually make:

Today, Jedda is sickening and, at the same time, laughable in its racism. (47)

In the Chauvels' story, however, Marbuk is not rebelling against white colonial rule. His important relationships in the film are with the Aboriginal characters. The white characters are in a different part of the film altogether, in the back story of Jedda.

Langton does not refer to Mudrooroo's view at this point in her book, although, strikingly, they both refer to the Tarzan story, but in quite opposed ways. For Mudrooroo, Marbuk is Tarzan - "a sort of Tarzan in black face" (Continuum) but for Langton, Tarzan "is the colonizer", while "Marbuk's equivalent is King Kong" (49). It's hard to see them as talking about the same film. As it's now available on DVD, you can see it yourself and form your own view.

There are also clips from the film available, again at the australianscreen site.

Robert Tudawali and Ngarla (not her real name) Kunoth in Jedda (Charles Chauvel, 1955)

Now we come to the revival of Australian Cinema in the 1970s and one of the most significant of the new films of that time: Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971). Marcia Langton does not mention it in her book, but no doubt she would have found a way of turning it into more colonialist propaganda. I myself have negatively criticised the film for what I see as its exploitation (ASE 2003). And certainly the film-makers are not only not Aboriginal, they are not even Australian. Roeg is a Brit who only came here to make this one film, based on a screenplay by an English playwright Edward Bond, who in turn based his work on that of English novelist James Vance Marshall.

However, the narrative places an Aboriginal boy squarely at the centre, together with an English girl, who also has no name. He is on a 'walkabout' - which a card at the beginning of the film explains that he must spend a period alone in the bush, subsisting by his own resources, and - I presume, and its a big presumption - meant not to communicate with anyone. But he meets the English girl and her little brother (played by the director's son, who is now a producer himself) and it's obvious to him that they will not survive unless he provides them with water and food. Not only that, but he becomes sexually attracted to the girl, and, in the climax of the film, performs a (genuine) courtship dance. But he is unsuccessful and - somehow - dies, apparently in some form of suicide.

As you will have seen if you watched the clip to which I referred you (in connexion with Journey out of Darkness) from Darlene Johnson's Gulpilil: One Red Blood, David Gulpilil, when asked why his character dies in Walkabout, replies that he doesn't know, and that he thought that he should have continued his journey. In my reading, he dies because of a double failure: he has failed to complete the 'walkabout' test (as defined by this film), and he has also failed to get the girl. And perhaps thirdly, and more subtly (and I'm only speculating) because he has given away some secret business in performing the dance.

But look at the same event from another angle, and you see a heroic self-sacrifice. The boy could clearly have completed his task, but he chooses to abandon it in order to rescue the helpless whites. He saves their lives, and loses his own - though the relationship between the two is complex and not made explicit.

Unfortunately, the National Film and Sound Archive's site lets us down this time. You'll just have to buy the DVD: it's well worth the price.

David Gulpilil showing the way to Luc Roeg and Jenny Agutter in a publicity shot for the film. This is definitely not a scene in the film. This must be an early poster for the film (that I found on the imdb.com website), as the young main actor (in his first film) is not named, and the blurb is bullshit.

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (Fred Schepisi, 1978) is not a pleasant film to consider from the point of view taken here. Homicidal black goes berserk and murders women and children with an axe. Schepisi's second feature, after his autobiographical The Devil's Playground (1976), and the first of two of Thomas Keneally's novels to be cinematised. (The other one won an Oscar.) If you were going to watch just one clip, you might profit more from watching the conditions that drove Jimmie mad, rather than the scene in which he reacts violently. I'm referring to him constructing perfect post-and-rail fences in the rain, after being stood over by the character played by West Australian actor Tim Robertson. The NFSA has made three clips available here - the first one showing the threat made by the white farmer, Healey - right at the end.

Tommy Lewis (aka Tom E. Lewis) as Blacksmith (whom Kenneally based on real-life murderer Jimmy Governor). Lewis is credited as co-writer on a short doco about himself shot and directed by Ivan Sen, Yellow Fella (2005).

Blackfellas (James Ricketson, 1993) is a West Australian production. It's based on the novel Day of the Dog by WA writer Archie Weller, in turn based on his own experiences, including encounters with the law and time inside. The nominal hero is played by John Moore, who was also the lead in another WA film (Zombie Brigade) - he might be the only one to do this twice - but the real standout performance is from David Ngoombujarra as 'Pretty Boy' Floyd. He gets one of the greatest lines an actor has ever been allowed to say in a film, as he dies by 'suicide by police' so that the other main characters can escape unnoticed. He says: 'Free. Free. Free as a fuckin' bird.' Ricketson is not Aboriginal, but sympathetic, and has made a film, which, tho a lesser achievement, can be considered in the same context as Jedda, in my opinion, in presenting a genuine (Aboriginal) hero.

There's no clip on the NFSA site. I wish I could make available a copy of White Fellas Dreaming for you. The best bit is in that. I'll clip a still or two.

|

|

|

|

Floyd sees that the only way John Moore's and Jaylene Riley's characters can get away is if he creates a distraction - and he is mortally wounded, so he pretends to draw sixguns (which he does not have) and gets shot dead. As this climax is prefigured earlier in the film, and as the first instance is more brightly lit, I'll attempt to show you that sequence.

|

|

|

|

Jindabyne (Ray Lawrence, 2006) is at least two films. (Australia, Baz Luhrmann, 2009 is at least three!) In one of its aspects, the film is a kind of thriller. A sinister killer (Chris Haywood) abducts and we assume sexually interferes with a young woman before dumping her naked dead body in a mountain stream. This character hangs around the periphery of the other stories, at one point appearing to threaten the principal female character Claire (Laura Linney) and so giving the film its crime/thriller characteristics (Jindabyne#1).

The body is discovered by four men who are on their annual fishing weekend - when they get away from their everyday lives, jobs and partners. At the centre of the film are the four pairs of relationships between the four men and their partners (Jindabyne#2). This of course recalls Ray Lawrence's first feature film, Lantana (2001) with its five or, I argue, six complex and inter-related pairs. It's a family melodrama.

The reason for discussing this film in this context is that the woman who is abducted, murdered and dumped is Aboriginal (Jindabyne#3). Not only that, but one of men's four partners, Carmel, is played by well-known Aboriginal actor Leah Purcell. So two issues arise. The men leave the body in the stream and continue with their fishing weekend. Would it have made a difference had she not been an Indigenous person? And secondly, when Carmel's partner Rocco 'defends' her (as an Aboriginal) and breaks the main character's nose, her reaction is anger: she says she can look after herself. The last third of the film is mostly about Laura Linney's character's attempts to reach out to dead girl's family (reminiscent of a similar situation in Australian Rules), including her presence at a smoking ceremony.

Initially, I saw this as a mainstream film trying to include Indigenous issues in a 'meaningful' way. It's my cynicism that makes me put that in scare quotes. My first reaction to the film was something like anger - that they had included the Aboriginal issue as a way of increasing the cultural capital of the film. But I'm just being silly: criticising the film for not being some other film. It simply does have this Indigenous issue as a central element. And Lawrence handles it as sensitively as he can.

Once again there are clips available on the australian screen website.

There are many more such films to talk about. It would be interesting to consider, for example, all of the films in which David Gulpilil has appeared. He is such a significant figure in Australian cinema that it would be revelatory. But I'll conclude for now with Beneath Clouds (Ivan Sen, 2002). I think it's not just the best film in this area - and the best directed by an Indigenous director - but among the best ever made in this country by anyone. There are clips and discussion again on the australian screen website. But I seriously suggest you buy a copy of the DVD, sit down and really pay attention to the film. Sen was a stills photographer before moving into film, and it shows in the beauty of the cinematography by Allan Collins. He, Sen, also wrote and performs some of the music. The film is quite outstanding.

I wrote most of this a couple of years ago. Since then, there's been a development which is another whole topic in this area: the emergence of Indigenous film-maker directors. I won't attempt to say what effect this has had - I'll leave that to you. I'll just list some of the significant productions.

Tracey Moffatt's beDevil appeared in 1993 (and she had made some short films) but it was easy to see it as a sport, firstly because it was itself made up of three unrelated short films, and secondly because Moffatt works mainly in photography and video rather than in the mainstream of the film industry. Before that, Brian Syron had directed Jindalee Lady (1992) which is claimed to be not just the first film directed by an Australian Aboriginal but also the first to be directed by any First Nations person.

Various anthologies gave Indigenous people the opportunity to direct short films which were seen by large audiences, on television, for example: From Sand to Celluloid (1996), Shifting Sands: From Sand to Celluloid Continued (1998), Crossing Tracks (1999), Unfinished Business: Reconciling the Nation (2000), On Wheels (2000), Dreaming in Motion (2002), Dramatically Black (2005), Bit of Black Business (2007).

Rachel Perkins directed Radiance (1999), One Night the Moon (2001), Bran Nue Dae (2009) and the telemovie Mabo (2012).

Ivan Sen followed Beneath Clouds (2002) with an American film Dreamland (2009), but has since returned to Australia to make Toomelah (2011) and Mystery Road (2013). His next film was a sequel to that called Goldstone (2016). His next film is set to be This Winter (tba).

Richard Frankland has made Stone Brothers (2009) which he wrote.

Warwick Thornton directed Samson and Delilah (2009) which he also wrote and shot. He has also directed short films and worked as cinematographer on a large number of films.

Bibliography

Collins, Felicity & Therese Davies 2004, Australian Cinema After Mabo, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Gillard, Garry 2008, Ten Types of Australian Film, second edition, Murdoch University.

Gillard, Garry 2006, 'Crocodile Dundee: "like a Tarzan comic"', Screen Education, 44: 125-128.

Gillard, Garry 2005, 'Signs, lines, tracks and trails: Rabbit-Proof Fence', Screen Education, 40: 119-122.

Gillard, Garry 2004, 'The Tracker: more than the sum of its types', Australian Screen Education, 34, 2004: 115-119.

Gillard, Garry 2003, 'Walkabout: simply a road movie?', Australian Screen Education, 32, Spring 2003: 96-99.

Gillard, Garry 2002, 'Perspectives on Radiance', Australian Screen Education, no. 29, 2002: 169-182.

Johnson, Colin [Mudrooroo] 1987, 'Chauvel and the centring of the Aboriginal male in Australian film', Continuum, 1, 1.

Jedda links and references

Jennings, Karen 1993, Sites of Difference: Cinematic Representations of Aboriginality and Gender, Australian Film Institute, Melbourne.

Langton, Marcia 1993, 'Well, I heard it on the radio and I saw it on the television ... ' An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the politics and aesthetics of film-making by and about Aboriginal people and things, AFC, Sydney.

McKee, Alan 1997, 'White stories, black magic: Australian horror films of the Aboriginal', Aratjara: Aboriginal Culture and Literature in Australia, 28.

Muecke, Stephen 2001, 'Backroads: from identity to interval,' Senses of Cinema, 17, Nov-Dec [online]; reprod. on the Backroads DVD.

Malone, Peter, 1987, In Black and White and Colour: A Survey of Aborigines in Australian Feature Films, Nelen Yubu Missiological Unit, Jabiru, N.T. and Leura, NSW.

Murray, Scott ed. 1995, Australian Film 1978-1994: A Survey of Theatrical Features, editorial assistants Raffaele Caputo, Alissa Tanskaya, 2nd edn, Oxford University Press in association with the Australian Film Commission and Cinema Papers, Melbourne; rev. and expanded edn of: Australian Film 1978-1992.

Palmer, Dave & Garry Gillard 2002, 'Aborigines, ambivalence and Australian film', Metro, 134: 128-134.

Palmer, Dave & Garry Gillard 2004, 'Indigenous youth and ambivalence in some Australian films' (second author, with Dave Palmer), JAS, 82: 75-84.

Pike, Andrew & Ross Cooper 1998, Australian Film 1900-1977: A Guide to Feature Film Production, revised edition, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, first publ. 1980.

Routt, William D. 2002, 'More Australian than Aristotelian: The Australian Bushranger Film, 1904-1914', Senses of Cinema, 18, Jan-Feb.

Simpson, Catherine 1999, Article on Radiance (28-31), and interview with director Rachel Perkins (32-34), Metro, no. 120.

Turner, Graeme 1988, 'Breaking the frame: the representation of Aborigines in Australian film,' in Anna Rutherford ed., Aboriginal Culture Today, Dangaroo Press-Kunapipi, Sydney: 135-145.

Verhoeven, Deb, 'Bitter Springs', Senses of Cinema, online.

Garry Gillard | New: 12 June, 2009 | Now: 18 November, 2019