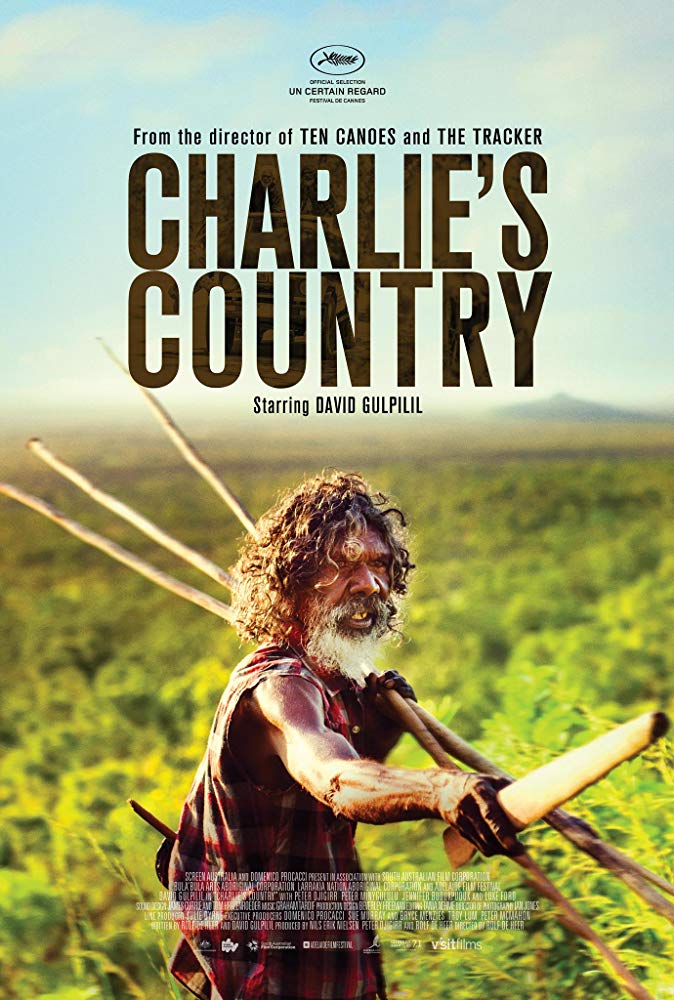

Charlie's Country (Rolf de Heer, 2013) wr. Rolf de Heer, prod. Nils Erik Nielsen, dp Ian Jones; David Gulpilil, Luke Ford, Ritchie Singer, Peter Djigirr; 'tragi-comic portrait of one man's struggle to define himself as an Aboriginal in modern Australia'; premiere Adelaide FF October 2013; 107 min.

Rolf de Heer is not in the entertainment business. Nor is he really a maker of art films - tho I have myself included him in that category in past writing. Nor is he a documentary maker - but I think most of his fiction films tend to be closer to documentaries than anything else.

This film is not a bio of Gulparil (as Jack Thompson calls David Gulpilil [v. Rielly, below] and as I'm fairly sure he calls himself in Ten Canoes) — but it is certainly based very closely on the kind of life he was leading in and near Darwin close to the time the film was made in 2013. He did drink in the long grass, he did go to hospital, and he did go to prison. (Tho it should perhaps be said that Gulparil went there not as a result of an ideological statement, as Charlie does, but for domestic violence.)

High Ground (Stephen Johnson, 2020) which is about to be shown in Australian cinemas as I write, was to have been Gulparil's last film, but he is dying - ten years younger than me. Even more sadly, he is dying in Murray Bridge in South Australia. There is a scene in Charlie's Country between Gulparil and an older man in a wheelchair, whose kidneys are shot. Charlie muses on the fact that the old man is not going to die in his own country, with no-one to look after him when he is dead. And now the same thing is going to happen to Gulparil himself - except that he will die of lung cancer, from a lifetime of smoking tobacco and what he calls ganja. He was given six months to live in 2017. On 29 February 2020, I haven't yet heard that he's dead. I think it will be widely announced. He is a great Australian. ... I hope he goes back to Ramingining before he dies.

Jane Howard:

Charlie (Gulpilil) lives in a remote Aboriginal community in Arnhem Land, where he and the other men of the community struggle with cultural ties in world dominated by white law and both deliberate and incidental racism. ... De Heer's film is a slow indictment of the colonialist relationship between white law and Indigenous people. It is a film you need to settle back into and experience rather than try and get ahead of the story. ... de Heer asks his audience to experience and reflect on Charlie's life and this complex clash of cultures. ... The steady pace of de Heer's direction is built upon Ian Jones's cinematography and Tom Heuzenroeder and James Currie's sound design. Jones's camera is often motionless and there is a sense of stills photography to the work: time for your eyes to search the scene and embrace the greenery of Arnhem Land, even as the action moves off screen. ... There is a sense of directionless[ness] in much of the film: it feels much longer than its 107 minutes, and we're not quite sure where de Heer is taking us, or how far through the story we are. But while this is essentially a small and contained journey of one man, through this simple story is a story of the complexities impinged by hundreds of years of colonialist rule. Jane Howard, The Guardian.

David Rooney:

... delicate but powerful film that functions as both a stinging depiction of marginalization and as a salute to the career of the remarkable actor who inhabits almost every frame.

Equal parts ethnographic and poetic, this eloquent drama's stirring soulfulness is laced with the sorrow of cultural dislocation but also with lovely ripples of humor and even joy. ...

While the story is fictionalized and its dialogue improvised (in English and the Yolngu language of the setting), its parallels to Gulpilil's recent past make it alive with authenticity. And yet, the film's observations about spiritual resilience in the face of white colonization and irreconcilable societal imbalance enrich it with emotional universality. It's the most affecting depiction of contemporary Aboriginal experience since Warwick Thornton’s Samson & Delilah. David Rooney, The Hollywood Reporter.

Eddie Cockrell:

The tangled tale of Aboriginal relations in Australia is rendered richly personal in director Rolf de Heer’s 14th dramatic feature. Anchored by the charismatic, tragicomic performance of indigenous icon David Gulpilil ... this atmospheric and cautionary tale of a ‘Blackfella’ caught between two cultures has all the makings of a solid art house performer. ...

Since his 1971 debut at 16 in Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout, Gulpilil has developed into an actor capable of mischievousness and gravitas, often within the same shot. His well-publicized bouts with alcoholism and the law haven’t significantly tarnished his reputation, and represent the embodiment of the societal tensions addressed in the film. So too, the Dutch-born de Heer has built a solid reputation as a filmmaker not so much fascinated as moved to modest yet probing action by social friction and injustice (his earliest major success, 1993’s Bad Boy Bubby, was the first of four of his films to be selected by Cannes). Eddie Cockrell, Variety.

Derek Rielly 2019, Gulpilil, Macmillan.

Garry Gillard | New: 18 February, 2014 | Now: 29 March, 2022