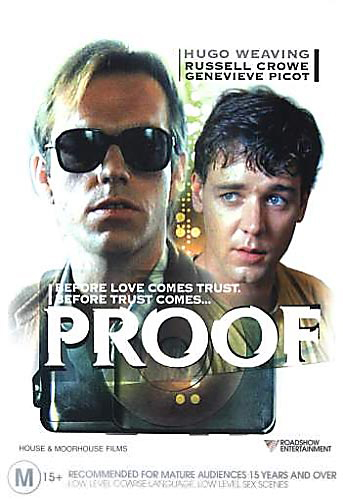

Proof (Jocelyn Moorhouse, 1991) Hugo Weaving, Genevieve Picot, Russell Crowe, Heather Mitchell; 86 min.

This is a gem: an insightful take on relationships between men/men/women in Australia, this is beautifully structured, and just a bit metafilmic. In 2016, NFSA announced it was planning to restore it for digital projection.

Jocelyn Moorhouse directed only this one Australian feature film before going to the USA where she directed How to Make an American Quilt (1995) and A Thousand Acres (1997). She returned to Australia to make The Dressmaker (2015).

If there is a kind of movie I like better than any other, it is this kind, the close observation of particular lives, perhaps because it exploits so completely the cinema's potential for voyeurism. There are not good or bad people here, simply characters driven by their needs and insecurities into a situation where something has to give. What could be more interesting? Roger Ebert.

Titles are intermittent with ('Martin's') photos. The main credits appear before the main title: PROOF. The first scene follows.

Exposition. Opening in medias res. The film opens with Martin walking down a shopping street. He knocks into people, is wearing glasses, and holding a cane, but hanging from his belt is a camera: establishing 1. Martin is blind 2. He doesn't care much about other people 3. There is something odd about him. Next scene is Andy taking out garbage behind the restaurant where he works. There is a cat, called Ugly, which Andy feeds, establishing he is a caring person. Martin comes down the lane, while Andy is having a smoke. Martin knocks over bottles, crates, continues. Andy discovers that the accident has apparently crushed Ugly to death. It starts to rain.

Martin arrives home with purchases, puts things down, lights gas fire, takes shirt off. Celia is discovered sitting, watching him. He hears her ashing her cigarette. She has already fed the dog. She offers to describe his photographs. He goes to the safe, she accompanies him. He puts his hand over her face. He gives the money she asks for. She offers to cook his dinner, but he says he's eating out, he won't tell her where. She leaves, putting the ashtray where he will knock it over. (Although we see two or three of Celia's act of 'random cruelty', we never see Martin involved in the results; whereas we always sees the results of Martin's cruelty as he inflicts it. His actions occur in discourse, Celia's actions occur in space.)

Martin sits in lounge chair, still in singlet, we hear house noises, it's raining still.

Flashback to Martin aged 7*, going into his mother's bedroom and feeling over her face. She wakes as he gets down to her breast.# She tells him off.

* [Film released 1991, in production say 1990. Martin is 32, therefore 'born' say 1958. His mother's gravestone says she died 1965, when he would have been 7.]

# [Martin's attitude to the breast is different to that of Charles, the main character in Man of Flowers (Paul Cox, 1983). As a child, he, Charles, puts his hand down the cleavage of a middle-aged woman (his aunt?), in a kind of fascination. As a man, he does not have sexual relations with women, but does admire the female form. He pays a young woman to expose her body for his visual pleasure (although he does not touch her), and he enjoys feeling the shape of a sculpted woman. He has sublimated his sexual desire into aestheticism, whereas Martin has completely suppressed his. What a pity: his so-well-trained fingers could have given him such a great deal of the kind of pleasure enjoyed by Charles Bremer (played by Norman Kaye in Man of Flowers).]

Martin in restaurant. He can't get served. (The waitress is played by Saskia Post.) To get attention Martin pours wine on the tablecloth. He orders. Andy sees what happens and is amused.

Andy leaves work out the back way, has a cigarette. Martin comes out of the toilet. Andy tells him he has to pay. Martin says his meal never arrived. Andy tells him he killed Ugly. Martin feels the cat in the bin. Martin finds he's not dead. Martin is to take him to a vet. Andy gives him a lift. They sit in the waiting-room. Martin gives Andy the cat, and Martin takes a photo of first them and then everyone in the waiting-room. Then the vet giving treatment. Driving home, Andy tells Martin a blind photographer is the 'weird sight of the week'. Martin tells Andy his mother gave him a camera. He 'thought it would help me to see'. Andy: 'See you round.' Martin: 'So to speak.'

Back in the restaurant, Andy preparing food. Martin has come to see him. To show the photos. Martin wants descriptions of each photo, in under ten words. Martin types labels for each photo. Andy: 'Why'. Martin: 'Proof'. Andy: 'Of what?' Martin: 'That what's in the photograph is what was there.' Martin tells Andy what was in the waiting-room, from the sounds and feelings. 'This is proof that what I sensed is what you saw through your eyes. The truth.'

Later, in the restaurant, Martin runs through some photos checking the labels are correct. Martin: 'Like your style: simple, direct, honest.' Asks if Andy would do this on a regular basis. Andy says no. Martin: 'Andy, you must never lie to me. Andy: 'Why would I do that?'

In a flashback, mother describes the weather to Martin, who wants to know if the man is there. Mother says yes, raking leaves. Martin can't hear him, says he was never there. Mother asks 'Why would I lie to you?' Martin: 'Because you can.'

Back in the flat, Celia is waiting for Martin. 'What's that smell?' 'I'm baking a cake.' 'What's that going to cost me?' Celia is turning 30 today. 'You have to admit to being a woman'. But Martin 'wouldn't know about that', implying that he is a virgin. She wants Martin to take a photo of her in her new blouse. She wants Martin to feel her (satin/silk?) blouse, puts his hand on her breast. 'You don't get a birthday present from me, Celia.' ( = We won't have sex.) 'You enjoy humiliating me.'

In the park, diegetic sounds, Martin puts a leaf out, snaps it. Bill, the dog, has been let off his leash. Cannot be seen. Martin calls, Bill comes.

In the restaurant, Andy describes photos. There is one of Celia. 'She's OK-looking.' 'Celia has no heart. A vile woman. I hate her.' Andy suggests they go to the drive-in. A lout getting into the car next door looks at what he thinks is a couple of poofters.

Andy is in the shop. Meanwhile, Martin checks out the car and its contents. He ends up at the window, so that he seems to be staring at the lout (or 'punk' [in the credits], played by Daniel Pollock, who was in Romper Stomper with Russel Crowe). Martin holds up some condoms he's found in the car. Punk bends aerial. Girl jumps on car, etc. Andy comes back, a fight develops, which Andy is losing. Andy gets into car and they escape with Andy driving from the passenger side. Cops in pursuit. They are pulled over. They stop but crash into the back of the police car. The cop tells Andy Martin has gone blind. A doctor examines M's eyes: he's been blind all his life. 'What were doing driving a car?' 'I forgot.' Much hilarity later when Andy and Martin are free, back in the car. Andy asks why he 'hides them'. 'Just defective tissue. Look at my eyes, they don't look back.'

In the flat, Martin gives Andy port. 'Who's that in the photograph?' It's M's mum. Andy describes the photo: they're in a park, long fingers, 29, pale, he has short hair.

'She always wanted an ordinary child ... she got me.'

'One day I might show you a photograph. It was the first one I ever took. I was ten. It's not much of a photograph really. It's just a garden that was visible from one of the windows in our flat. But it's the most important photograph I've ever taken. Every morning and every afternoon, my mother would describe this garden to me. I saw the seasons come and go through her eyes. I used to question her so thoroughly, always trying to catch her in a lie. I never did. But by taking the photo I knew that I could. One day.'

'Why would your mother lie to you?'

'To punish me. For being blind'

'Does it really matter if she lied to you about a ... garden?'

'Yes. It was my world.'

Celia is looking through M's photos in M's flat, finds bits of Andy in them. She assembles them on a table to make a composite of Andy. Andy knocks on the door. Celia and Andy meet. Andy has seen C's photograph. Celia says Martin doesn't know the meaning of the word 'love'. She tells Andy Martin is in the park, 'walking the fleabag'. Andy is puzzled about Celia.

In the park, Bill sees Andy, comes to him, then on to Celia. Martin calls Bill, but Celia holds him. Martin takes photos in a circle. Andy dives out of sight behind a tree. Then Celia lets the dog go. Andy is even more puzzled.

Celia picks up the next lot of photographs, goes to the flat where she finds both Martin and Andy. Martin 'introduces' them. Celia has picked up the photographs. Martin tells her never to do it again. Andy is showing sexual interest in Celia, as indicated by the reverse shot of her legs in conjunction with the vacuum cleaner hose pipe. She smiles back. Meanwhile Martin is telling Andy the current lot of photos might reveal where Bill goes in the park. Andy looks at the photos, sees himself ducking behind the tree. Andy lies to Martin. Celia is amused that Andy is lying to Martin: they are complicit. Celia suggests the 'other dog' in the photograph is a 'bitch on heat'.

Outside the two men discuss Celia: she's 'like a rare disease'.

Later, in the flat, Celia takes a polaroid photo of Martin on the toilet, threatens to display it somewhere embarrassing to Martin 'What do you want?' '... for the photo? Money?' 'I want your company, for one night.'

So, they are in the concert hall. Beethoven's third begins, and Martin is deeply moved. Inappropriate camera angles, like a TV broadcast, btw. Martin has his glasses off so we can see his reaction. He feels over his heart. Celia is weeping.

Later, Martin thanks Celia: 'That was an experience I will never forget.' He asks for the photograph but she tells him the 'night's not over yet'. They have gone to her flat. He sits, and the camera - when the lights come on - moves around behind Martin and we see photos of him everywhere. She says she photographs 'things I love'. She tells him he doesn't know how fond she is of him. He says he's 'getting a fair idea'. She brings him his 'favourite cold meats'. (Strange phrase.)

'For so long I've wanted you in my house. And now you're here.' She unbuttons the same blouse as before.

'I never knew my father. And my mother's died ten years ago. So now there's only me. And you.'

Lot in common. Both motherless.

'Did you ever get the feeling you were being watched?'

'All my life.'

'And you never knew it was me?'

She asks him if he's a virgin, at 32.

She puts his hand on her naked breast, takes his glasses off, pushes her breasts against his face, takes her blouse off, undoes his fly. They kiss. He says he 'can't'. Pushes her away, runs away, without stick, without glasses. He's lost. Celia comes up in the (BMW) car to drive him home, which she does. When they get there, she says he doesn't trust her. She says she's the only one he can trust. He says not. They talk of her leaving. And, finally, about enjoying it (their sado-masochistic relationship).

Inside, in bed, he cries.

Flashback to his mother telling him she's going to die, won't be able to describe the garden. Young Martin says she's doing it to get away from him, she's not telling the truth, he'll never believe her. Then, her coffin, which he feels, knocks on. He says it's 'hollow'.

Andy goes to M's. The door is open. Celia is there, cleaning. Martin is at the library for the blind. Celia says he can look in the bedroom. There are dirty books. Andy follows Celia into the bedroom (surprise!). Celia says Martin hates her, loves Andy. Celia reminds Andy he lied - 'for me', she says, and repeats, adding 'in case'. She sits, then lies on the bed.

Andy goes to Martin in the park. Martin photographs a leaf, because Andy told him it was there. 'I trust you, Andy.' 'Maybe you shouldn't.' I'm no good at responsibility, Martin.' His bosses have said he has an untrustworthy face, changes jobs, moves around, is a black sheep. But Martin finds the leaf.

Celia puts the photo of Andy ducking behind the tree into Bill's collar. Martin goes to the vet's: he finds the photo. Martin reads the label, but the vet tells him that Celia and Andy are in the photo. Meanwhile, back at the flat, they are about to have sex. Martin goes home. Andy puts his pants on. 'Who else is here?' Martin hears Andy put his shirt on, pick his stuff up, grabs him as he goes past. 'Celia and I are in love.' Martin tells them to get out. They do, goes to C's place. Andy sees all the photos, everywhere. Reaction. Celia gives Andy tea. Reaction. 'He won't forgive you. Not now.' He leaves.

Martin in cemetery, is led to headstone, feels the inscription with his mother's name and date of death. Asks if empty coffins are ever buried. The attendant reassures him

Back at M's flat, Celia is still doing stuff for him. Martin apologises for tormenting her, fires her. She says he's being ridiculous. 'Not any more.' She throws the key in the water in the sink. He's arranged for another 'cleaning woman'. He's written her a reference. She kisses him goodbye, cries. She says whenever Bill doesn't come, he'll think of her. She leaves, putting the hatstand in front of the door.

At the restaurant, Andy looks at the empty table where Martin sits.

Martin comes home. Andy is waiting outside. Martin asks him in. Andy doesn't have time. Needs money to go into business. Martin says Andy 'can't know how important truth is to me'. Andy says that ppl lie, but not all the time, that the only thing he lied about was Celia. Martin asks how he can believe him. Andy says he can't. Andy says Martin tells the truth, his whole life is the truth. 'Have some pity on the rest of us.' Martin asks him to look at THE photo. Andy says there's a man in the garden, holding a rake, birdbath, man looks old and 'kind'. 'It's a nice photo, Martin.' 'Keep it.' Martin says he might drop into the restaurant tomorrow. Andy says he'll be there.

BUT WE DO NOT SEE THE PHOTO.

Young Martin is sitting at the window. It's raining. He puts his hand up to the window.

END.

Notes written 14 April 2002.

1

The exception proves the rule - in the older sense of the word "prove": it tests the rule.

The rule in human existence is not truth, but its opposites: ignorance and forgetfulness. Truth is the word for those exceptions that are remembered or revealed. Each one is the result of some test.

One artistic metonym for human being-in-the-world is Martin, the main figure in the film Proof (1991, dir. Jocelyn Moorhouse). In his physical blindness, he stands for us. For him (as it happens), the test is visual. And as he literally cannot see himself, he is dependent on others for the revelation of each truth. (Seeing, blindness, revelation, truth - all these are metaphors - and not only in this film.)

It does not occur to all of us to be sceptical about the taken-for-granted. In Martin's case, there is a psychological stimulus. His primary - in fact his only - relationship, aged (about) 7, is with his mother. She dies - but has time to tell him that she is going to, and that she won't be able any longer to describe the garden (his 'world') for him, as he has done twice every day of his life. Young Martin cannot accept the revelation of this particular kind of truth - and says she's doing it to get away from him because of his blindness, she's not telling the truth, he'll never believe her. In the next scene, he is alone with her coffin, which he feels and knocks on. He says it's 'hollow'.

Martin's Cartesian scepticism is still active 25 years later and he is still searching for some agency he can trust to roll back ignorance, to reveal truth.

The only person in his life (as far as we can verify) is Celia, his 'cleaning woman' as he sees her (she wants to be much more), but unfortunately she is a female, and we know what happened last time he trusted one of them. Fortuitously, he meets Andy in a back alley (as you do), and a relationship develops in which Martin believes he has found a trustworthy revelator. (So Martin gets Andy to describe his photos, etc. etc.)

But even an antipodean art film cannot avoid the pressure to conform to the pattern of Hollywood's parallel plot lines (action + romance) - and romance ( = sex) interferes with the intellectual pursuit of truth - and Andy has it with Celia. (Sex, that is, though he does tell Martin: "Celia and I are in love." But no-one, they or we, believes that for a moment.) The interference consists in the result (of his desire - he has not yet fulfilled it) that Andy tells Martin an untruth.

There is an interesting complication in this untruth. Andy tells Martin that the photo shows Bill, Martin's 'seeing-eye' dog, with another dog, whereas in fact the photo shows Andy rushing behind a tree to conceal his presence on the scene. One of the complications is that Celia says that the other dog must be a 'bitch on heat' - obviously, by the way, a reference to herself. The other is that she later tells Andy that he has lied 'for me', she says, and repeats that, adding 'in case' (in case, that is, their relationship develops as it in fact does). But as the photo does not show Celia at all, let alone in the incriminating act of holding Bill from going to Martin - that it is a lie 'for her' is a lie.

There is a confrontation in the penultimate scene about Andy's deception. Andy points out that everyone lies, but not all the time, and that the only thing he lied about was his relationship with Celia. Martin asks how he can believe him. Andy says he can't. Andy tells Martin that whereas he (Martin) tells the truth, and that his whole life is the truth - most of us do not live like that. 'Have some pity on the rest of us,' he implores Martin.

After accepting Andy's confession that he has lied, Martin now puts his trust in him (as you do), and asks him to look at THE photo. This is what he has to say about it.

'One day I might show you a photograph. It was the first one I ever took. I was ten. It's not much of a photograph really. It's just a garden that was visible from one of the windows in our flat. But it's the most important photograph I've ever taken. Every morning and every afternoon, my mother would describe this garden to me. I saw the seasons come and go through her eyes. I used to question her so thoroughly, always trying to catch her in a lie. I never did. But by taking the photo I knew that I could. One day.'

So, in the penultimate scene of the movie, Andy describes the photo of the scene which Martin's mother described to him 25 years previously: there's a man in the garden, holding a rake, there's a bird bath, the man looks old and 'kind'. Because of the detail of the man and the rake, we are meant to come to know that Andy is telling the truth (as he has not been told what the photograph shows - and it has been locked in a safe). 'It's a nice photo, Martin,' says Andy. 'Keep it,' says Martin, as he no longer needs it. He now knows: 1. that his mother was telling the truth about the garden on that particular occasion when he took that photograph, and therefore, that 2. she was telling the truth as to why she departed from his life: she really did die, not just leave because she didn't like him. He has already tested the second claim to truth, in the fifth-last scene of the film, when he goes to the cemetery, and, having been guided to his mother's grave, reads the details on the headstone with this fingers. (This, by the way, suggest an equivalence between the photographic and the lithographic.)

In another scene, Celia forces Martin to spend an evening with her through the power of the photograph. She takes a polaroid of Martin on the toilet and threatens to embarrass him by exposing it, if he will not. Such is its graphic power that Martin does what she wants.

The film is overflowing with photography. (How the cinematographer must have enjoyed working on a film that was about "writing with light"!) But there is one - and only one photograph - that we do NOT see. It is THE photograph: the one that proves that rule. As artworks do, this one asks a question: Is that which is seen real? And it does not answer.

Proof in Jocelyn Moorhouse's film Proof (1991) is the kind inferred in the proverb: the exception proves the rule - in the older sense of the word "prove": it tests the rule. Martin, the main character, is a blind man who wishes to establish to his own satisfaction the truth of two propositions: firstly, that his mother did in fact die (when he was about seven years old) when she told him she was about to do so; and secondly, that a photograph he took at the time in fact shows what his mother says was in view of the camera that took it. Martin can be seen as operating in terms of A. J. Ayer's verification principle.

We say that a sentence is factually significant to any given person, if and only if, he knows how to verify the proposition which it purports to express - that is, if he knows what observations would lead him, under certain conditions, to accept the proposition as being true, or reject is as being false. (Language Truth and Logic)

As Martin, who took the photograph, cannot himself see it, his quest is to find someone he trusts sufficiently to describe the photo to him. This will provide the "proof" of the title, the test of his mother's veracity.

There is a link between the mother and the photo.

The first candidate for the trusted person is Celia. But Martin doesn't trust her.

Then, twenty-five years after M took the photo, he meets Andy. M paradoxically trusts A, even tho he lies to him.

Martin is a mise-en-abyme figure * - or, to put it another way, may be seen a metonymic in relation to the viewer of the film. (Any film?) One of the test the viewer applies to any film (any moment, any character) is that of plausibility: do they believe what they see? (Perhaps the most typical negative criticism hoi polloi make of a film they don't like is to say that it wasn't "realistic" - which is not a statement about stylistics but about belief.) In the same way, Martin needs to believe in the visual information. The fact that he can't personally see it just makes the situation more poignant.

* ['... a "mise en abyme" is any aspect enclosed within a work that shows a similarity with the work that contains it.' (8) '... any internal mirror that reflects the whole of the narrative in simple, repeated or "specious" (or paradoxical) duplication...' (43). Lucien Dallenbach, 1989, The Mirror in the Text, trs. Jeremy Whiteley with Emma Hughes from Le récit speculaire: essais sur la mise en abyme, Seuil, Paris, 1977.] Another way to think about "truth" is as revelation, as the absence of forgetting (a-letheia) or the elimination of ignorance. (The first of those ideas invites an excursion into Heidegger, which I can't do; the second might suggest an excursus on Platonic maieutics as exposing what was "already known". Or maybe not.)

Abstract. The film Proof thematises one of the fundamental aspects of the condition of film as such - with a postmodern quirk.

A. One of the fundamental aspects of the condition of film as such is to reveal some truth.

B. Philosophically, truth is aletheia: revealing concealing.

C. Some films thematise the revelatory aspect of their condition.

Such films reveal the truth that is at their heart in a visual way. A photograph may be seen to reveal a presence that was hitherto absent. (Cf. Blade Runner and Giuliana Bruno's paper. Cf. Blowup.) Or some other visual evidence may be employed. The Usual Suspects unconceals the fabrication constructed by the main character by showing a succession of images and texts in the key scene. (One should be able to think of films that use videotape and film in a similar way.) Strange Days uses a recording of experiental data (hard to describe this briefly) which can by played back in order to unconceal the identity of a key character.

D. Our film also thematises the revelatory aspect of its condition, but with an added dimension - twist, quirk, etc.

1. Our film draws attention to the possibility of aletheia at the outset - in its title.

2. But the protagonist is blind (from birth), and therefore can never see the visual evidence (the 'proof') which is at the heart of the film's meaning. (The protagonist shares his (only) name with another Martin: Heidegger. Coincidence?) The protagonist stands in for the film's viewer. His blind body is the film's body (Sobchack). In this film, the viewer will never see the truth revealed: it is a fundamental condition of this film.

3. The protagonist relies on his handy man, Andy. Andy gives him a hand. Andy is the means (the medium) of revelation. Andy stands in for the filmic apparatus. But - like any filmic apparatus - he cannot be trusted. (He is really Ambi: ambivalent, ambiguous.) Andy says himself that he loses jobs because he 'an untrustworthy face'. Martin, however, cannot see Andy's untrustworthy face. In their last scene together Andy actually admits that he has lied to Martin (about his relationship with Celia), and says that everyone lies - although not all the time.

4. The film's denouement appears to reveal the truth that Martin has sought all his life (that his mother was telling the truth, that she did love him). The film, however, actually reveals its fundamental condition by NOT revealing the photographic evidence to the viewer. The filmic apparatus, Andy, makes an aletheic claim - but, as we have seen, he cannot be trusted. The film ultimately refuses the 'proof' it appears to have offered.

Conclusion. Many films (all films?) offer to, pretend to, reveal some truth of some kind, but all the viewer ever actually sees is the filmic apparatus. This film reveals this truth, not in a crude way by laying bare the device (Shklovsky) but in the arc of its narrative, by showing what it does not show.

THE photo in Proof is a mise-en-abyme, as is its owner, Martin. The photo is mise en abyme for the screen, the cinematic apparatus; Martin is mise en abyme for the viewer. Proof is an archetypal film about film.

Compare other films about film: Targets, where the screen appears to shoot members of the audience; Persona, where the film shows its apparatus in three ways: starting up, breaking, and revealing the filmmakers (Bergman and Nykvist) at the end.#

# [Roger Ebert: "... Bergman allows his film to seem to tear and burn. The screen goes blank. Then the film reconstitutes itself. This sequence mirrors the way the film has opened. In both cases, a projector lamp flares to life, and there is a montage from the earliest days of the cinema: jerky silent skeletons, images of coffins, a hand with a nail being driven into it. The middle "break" ends with the camera moving in toward an eye, and even into the veins in the eyeball, as if to penetrate the mind.

The opening sequence suggests that Persona is starting at the beginning, with the birth of cinema. The break in the middle shows it turning back and beginning again. At the end, the film runs out of the camera and the light dies from the lamp and the film is over. Bergman is showing us that he has returned to first principles. "In the beginning, there was light." Toward the end there is a shot of the camera crew itself, with the camera mounted on a crane and Nykvist and Bergman tending it; this shot implicates the makers in the work. They are there, it is theirs, they cannot separate themselves from it."]

Notes written 14 April 2002

Garry Gillard | New: 23 October, 2012 | Now: 2 December, 2019